Ralph Vaughan Williams’ debt to nineteenth-century poetry

John Blackmore

‘The Lark Ascending’ by Ralph Vaughan Williams was premiered in Shirehampton, near Bristol, one hundred years ago this month. This ‘Romance for Violin and Orchestra’ has remained an immensely popular work to this day. It was voted the favourite Desert Island Discs track of all time in 2011, and has occupied the number one spot on Classic FM’s ‘Hall of Fame’ ten times since the poll’s inception in 1996.[1] The work’s popularity extends beyond British shores; when listeners to New York’s Public Radio Network, WNYC, were asked which pieces of music should be played to mark the ten year anniversary of the World Trade Centre Attacks, ‘The Lark Ascending’ was the second most popular choice, sitting between works by Samuel Barber and Bruce Springsteen.[2]

Why ‘The Lark Ascending’ occupies such a prominent place in public life is difficult to say. Perhaps the work’s power lies in its capacity to stun, or lull, the listener into a moment’s introspection. Its ethereal and restless qualities render it neither jubilant nor melancholic. Rather, the work is, by turns, contemplative and transcendent. The interplay between the solo violin part and orchestra deftly conjures the lark of the work’s title – a reference to the poem of the same name by nineteenth-century writer, George Meredith.[3]

Extracts from Meredith’s 1881 poem adorn the title page of Vaughan Williams’ manuscript. The twelve lines selected by the composer from the 122-line poem clearly shape the narrative of his musical setting. The lines come from the beginning, middle and end of the poem, and seem to have been chosen because they denote key moments in the bird’s ascent or song. First the lark ‘rises and begins to round’ (1), then his singing intensifies, ‘filling heaven’ (65) and ‘overflowing’ (69) the valley of the listener. Finally, the lark has risen so high that it is ‘lost’ (121) to the sight of the poem’s speaker but can still be heard in the poem’s final words: ‘and then the fancy sings’ (122).

Meredith’s poem not only influenced the story of Vaughan Williams’ musical setting; the poem’s formal properties were incorporated into the setting’s sound and structure. For example, Meredith’s rhyming couplets of eight-syllable (iambic tetrameter) lines imitate the short, repetitive and melodic song of the lark. Vaughan Williams’ short and recurrent violin phrases echo this. The motion of the lark as it rises through the air, ‘ever winging up and up’ (67), are also referenced in Vaughan Williams’ score, in successive ascending runs and scales. Meredith’s imagery regarding the timbre and volume of the lark’s sound is also recreated by Vaughan Williams dynamically. At first, the lark ‘drops the silver chain of sound […] In chirrup, whistle, slur and shake’ (2-4). Later, the speaker describes how the song is powerful and strong enough ‘to lift us with him as he goes’ (70). By the end, the lark might be ‘lost’ (121) from view, but its strains can still be heard, which is reflected in the interrupted cadence of the slowly fading solo violin at the end of Vaughan Williams’ score.

The success and popularity of Vaughan Williams’ ‘The Lark Ascending’ has long-since eclipsed that of Meredith’s poem from which it was derived. While often acknowledged as a primary source, biographers, critics and writers often plunge past Meredith’s poem in search of more enigmatic contextual details concerning the musical setting’s origin story, or the composer’s motivation. For example, Richard King has recently considered Vaughan Williams’ ‘The Lark Ascending’ through the lens of the composer’s experiences in the First World War.[4] Meanwhile, Andrew Green has looked at the work as ‘an elegy for Britain’s rural communities.’[5] It is important to recognize how such writers are drawn to largely unknowable details, which feed the mythology surrounding this popular piece of music. In contrast, Meredith’s poem provides a tangible and important source that has been frequently overlooked.

‘The Lark Ascending’ is perhaps the best-known example of how Vaughan Williams reinterpreted nineteenth-century poetry and presented it to new audiences. It is by no means an isolated example. Vaughan Williams set a great number of works by nineteenth-century poets to music, including Alfred Lord Tennyson, Christina Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Algernon Swinburne, Walt Whitman and, of course, William Barnes.[6]

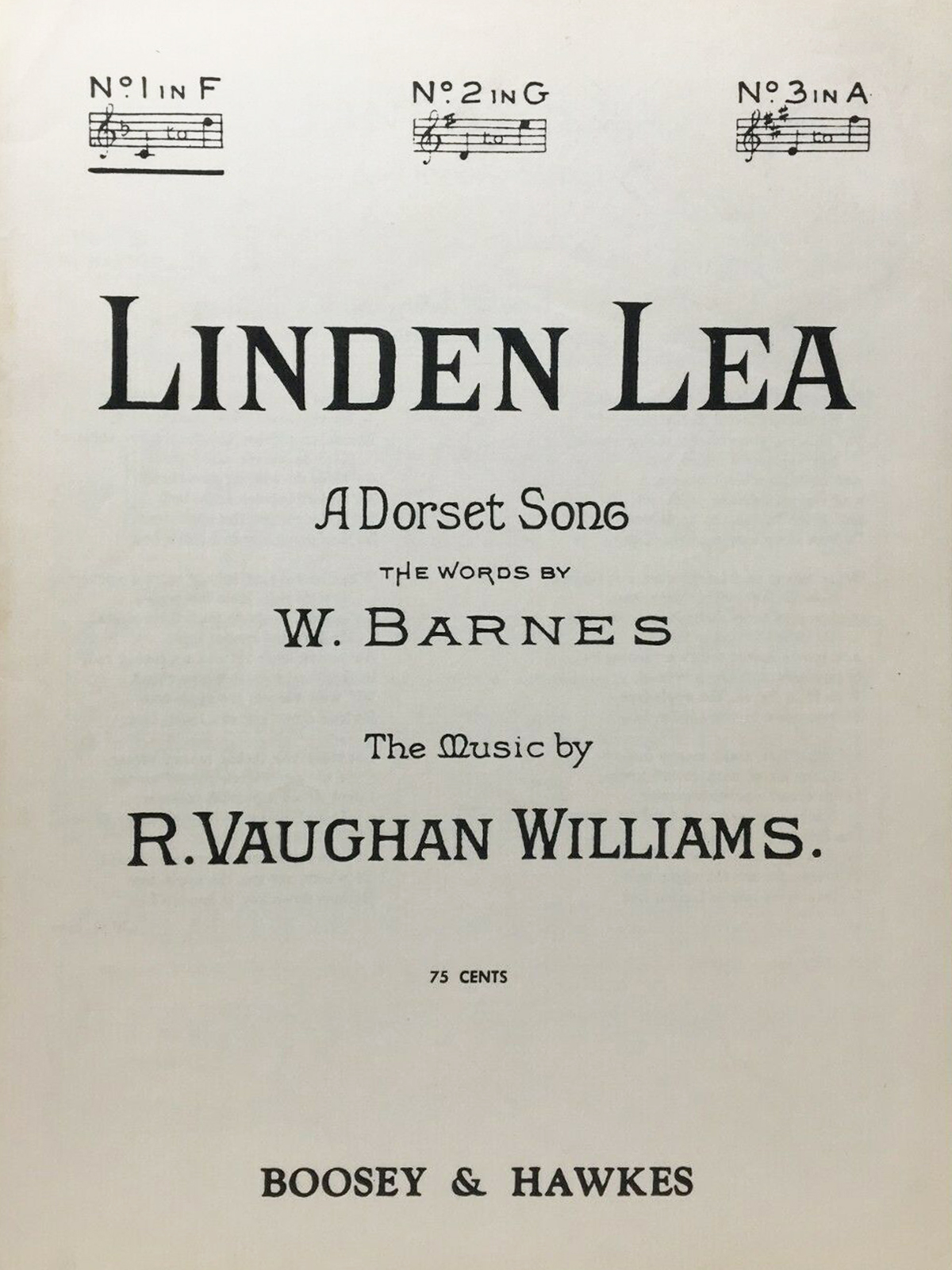

Vaughan Williams is known to have set four of Barnes’ poems to music: ‘Linden Lea’ (1901), ‘Blackmwore By the Stour’ (1902), ‘The Winter’s Willow’ (1903) and, much later, ‘In The Spring’ (1952), which was dedicated to the William Barnes Society. Barnes’ dialect poetry seems to have had an enduring appeal to Vaughan Williams, and one work in particular occupies an auspicious place in his list of compositions: ‘Linden Lea’ was Vaughan Williams’ first published work, and one of the most financially successful.[7] It is not clear why, or how, Vaughan Williams came to set Barnes’ dialect poetry to music. It is curious, though, to see how Barnes’ works, so firmly associated with life and language in one of England’s rural regions, sit so comfortably on CD sleeves and playlists alongside settings of works by poets that occupy a more national, or central position in public consciousness. In contrast, Barnes has, more often than not, been considered a marginal figure in nineteenth-century literature.

Just as with Meredith’s ‘The Lark Ascending’, Vaughan Williams’ setting of ‘Linden Lea’ has become better known than Barnes’ original. As a result, it has attracted new audiences to Barnes’ works, and – for better or for worse – has helped (re)shape relations between people and regional, rural spaces throughout Dorset, the South West, England and beyond.

Vaughan Williams’ most popular arrangements like ‘Linden Lea’ and ‘The Lark Ascending’ provide exciting opportunities to reconsider the place of nineteenth-century poetry in our everyday lives. The enduring relevance and appeal of Vaughan Williams’ musical settings owes a great debt to the literary works that inspired them. When we return time and time again to these much-loved musical settings, we also return – knowingly or not – to these earlier literary works.

Bibliography

- ‘A Wing and a Prayer: The Enduring Beauty of The Lark Ascending’, The Guardian, 2020 [accessed 10 December 2020]

- ‘Composers and Their Poets: Ralph Vaughan Williams’, Interlude, 2017 [accessed 11 December 2020]

- ‘December 2020’, Classical Music [accessed 10 December 2020]

- Heffer, Simon, Vaughan Williams (UPNE, 2001)

- ‘How the First World War Inspired Britain’s Favourite Piece of Classical Music’, The Guardian, 2014 [accessed 10 December 2020]

- King, Richard, The Lark Ascending: The Music of the British Landscape (Faber & Faber, 2019)

- ‘Kissing Her Hair: Twenty Early Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, Presto Classical [accessed 11 December 2020]

- Meredith, George, Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (Macmillan and Company, 1883)

- ‘New York State of Mind: Listeners Pick 9/11 Soundtrack to Mark Anniversary’, The Guardian, 2011 [accessed 10 December 2020]

- ‘War Composers - the Music of World War I. Ralph Vaughan Williams at War’ [accessed 10 December 2020]

- Richard King, The Lark Ascending: The Music of the British Landscape (Faber & Faber, 2019).

- ‘New York State of Mind: Listeners Pick 9/11 Soundtrack to Mark Anniversary’, The Guardian, 2011 [accessed 10 December 2020].

- George Meredith, ‘The Lark Ascending’, Poems and Lyrics of the Joy of Earth (Macmillan and Company, 1883) p. 64-70.

- King, The Lark Ascending, p. 8.

- Andrew Green, ‘Liberating the Lark’, in BBC Music, Vol. 29, No. 2, December 2020, p. 26.

- ‘Composers and Their Poets: Ralph Vaughan Williams’, Interlude, 2017 [accessed 11 December 2020].; ‘Kissing Her Hair: Twenty Early Songs of Ralph Vaughan Williams’, Presto Classical [accessed 11 December 2020].

- ‘Kissing Her Hair’, p. 5.

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | Barnes Night: A Celebration of the Life and Work of William Barnes

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | A Dorset Spring through the Poetry of William Barnes

11:00 till 12:30

Annual Service of Thanksgiving of William Barnes

Starts 00:00

Cerne Abbas Festival - William Barnes' Poetry Readings

13:00 till 15:00

Wreath Laying at the William Barnes Statue

10:00 till 17:00

William Barnes at Stock Gaylard Oak Fair 2026