The Folk-Lore of William Barnes

John Symonds Udal

I have been asked to write a short paper or article on "Dorsetshire Folk-Lore" for our "Year Book." But I feel some difficulty in doing so, for two reasons; first, because it is impossible in such a limited space to give any fair idea of what the folk-lore of the Dorset people consists; and, secondly, because I am myself just in the throes of publishing a larger work of that kind — a labour of love which has taken up a considerable part of my life's leisure time, and which I hope may, at no distant day, see the light. Any gathering together or hotch-potch of extracts from this work would scarcely be fair either to myself or to my subscribers.

But it has struck me that, perhaps, something based more specifically upon one of the greatest authorities that I have used for my own work might be justifiable, and even more acceptable to my readers. And that great authority is the late William Barnes — our “Dorset Poet,” who cannot now be remembered by very many of my readers in the flesh, but who is, and, has always been, a household word with our “Dorset Men in London.”

When, some fifty years ago, I myself began to collect items of the county folk-lore, it was in an interleaved copy of Barnes's “Grammar and Glossary of the Dorset Dialect,” published at Berlin for the Philological Society in 1863, that I jotted them down until it became too small to hold them. Again, it is in the interleaved pages of the " Glossary " part of it that I, to this day, continue to enter any new dialect words that I come across; which has rendered this little volume one of my most precious literary treasures.

But I wanted more than I could collect myself. So in 1881 I wrote to the then editor of the Dorset County Chronicle suggesting that a "Folk-Lore Column" might be opened in his journal, in which could be preserved such items of county folk-lore as might, in these days of greatly increased communication and Board School education be unrecorded, if not lost altogether. Of this the Editor courteously approved, and for some years his columns were the recipients of numerous items of the old peasant lore.

Amongst these early contributors William Barnes took a leading part, followed by myself and others who may still be known to the county. Gradually, however, this happy venture, like many similar ones, came to a close through want of contributions rather than from want of readers' interest; for that which is everybody's business soon becomes nobody's. But meanwhile what had been achieved in this way was most useful to my own work; and I cannot even now sufficiently express my thanks to the “Dorset County Chronicle" for the great assistance it has always been to me in this matter.

In its pages, too, appeared from time to time lists, in alphabetical order, of Dorset dialect words, which were the outcome of Barnes's desire to assist in that great work originated by the English Dialect Society, and which, after a score of years' incessant labour culminated, about the year 1898, in that magnificent work in six large quarto volumes, “The English Dialect Dictionary,” edited by Dr. Joseph Wright, F.S.A,— a work that has practically taken the place of all local glossaries, and to the preparation of which several Dorset men have made numerous and useful contributions. To this I, too, would have gladly contributed from my little store already mentioned, but that my absence at the other end of the world caused me to be unaware of its preparation; and it was not until some time after the actual appearance of the, great dictionary that I became aware that a very large proportion of my own collection of dialect words was to be found there. The remainder of my unpublished words I subsequently recorded in the "Somerset and Dorset Notes and Queries,"1 so that they, too, might find a permanent home.

Though Barnes had never, so far as I am aware, written specifically upon or made a subject of Dorsetshire folk-lore except in a few scattered, short articles, nevertheless he and his dialect poems were brimful of it. So is it any wonder, as my own collection of folk-lore had by this time largely increased, and I began to think of possible future publication, that 1 turned to him—with whom at that time I was well acquainted — with a view of getting him to write me some introduction to my own contemplated work? He was then approaching, his eighty-sixth year, and in very indifferent health, though his intellect was still keen and bright, and was mainly confined to his room, if not to his bed. He then wrote for me — without any knowledge of the actual materials I had collected, at his own leisure and in his own way, upon any odd ends or pieces of paper — what now forms his "Fore-say" 2 (as I am calling it) to my book — to my mind, by far the most interesting and valuable part of it. It is not often, I imagine, that an author carries about with him for over thirty years an introduction to a book which has not yet seen the light! But so it is. My long absence in the Colonies, which made it impossible for me to get my collection into any literary shape for publication, was the cause of this. At the same time the delay for so many years has enabled me to add a very considerable amount of fresh material.

It was about this time, too, that Barnes gave me an autographed copy of the new edition of his “Glossary” (with the Grammar) which had just been published in Dorchester in 1886 — in the earlier part of the year in which he died. It is somewhat strange that his daughter Lucy — the late Mrs. Baxter, of Florence, better known, perhaps, as “Leader Scott,” and who, under that name, had written the “Life of William Barnes,” the year after his death — should not have been aware that this new edition of the Glossary, upon which her father had so busied himself, had then actually been published; for in the Appendix II, to the “Life,” containing a list of her father's works in chronological order brought right down to date, she states: “1886 — A Glossary of Dorset Speech. Partly printed, but never published, as the author's death prevented the final revisions. That she was fully aware that he was engaged upon such a work is shown from p. 278 of the “Life, which happens also to refer to myself as having been of some assistance to him in sending him new words for the Glossary, which was always enlarging itself under his hand, and he returned the service by collecting legends and superstitions for Mr. Udal's contemplated work on the Folk-Lore of Dorsetshire for which, nearly ten years later, Barnes, at his request, wrote an introduction."

I may remark here that these “legends and superstitions” were mainly contributed to the Folk-Lore column in the “Dorset County Chronicle” already mentioned, where, of course, I saw and made use of them. She adds: "Folk-Lore was to him one of the most interesting subjects of investigation.”

In a letter to me from Florence, written about this time, Mrs. Baxter — in acknowledging some letters and other papers I had sent her relating to her father whilst she was engaged in writing his “Life,” — says:

"I am very pleased with . . . . your mention of his Introduction to your work of Folk-Lore, as it explains what was a dark saying in his notes, ‘Writing on Folk-Lore,’ for I had no clue to the M.S., nor its ultimate destination.” I hope I may be pardoned for adding the following expression of that sweet and simple filial piety which illumines Mrs. Baxter's " Life " of her beloved father which concluded her letter to me. “The office of biographer has been to me a work of love, though I feel very much how inadequate one woman's mind is to interpret the many deep phases of his wondrous intellect, as well as the simple purity of his daily life. It can at the most only be a sketch."

With reference to this “Introduction" or “Fore-say,” — as I am sure that Barnes himself would have preferred to call it, for Latin derivatives were obnoxious to him — I may as well give his definition of the subject-matter. It is generally known, I think, that the word “Folk-Lore” itself (meaning literally “the learning of the people”) was coined by the late William J. Thoms, F.S.A., the first editor of “Notes and Queries,” about the middle of the last century. As stated in the Introduction to the last edition of the “Handbook of Folk-Lore," published by the Folk-Lore Society in 1913, this word was intended to replace the earlier and commonly used expression, “popular antiquities.” However, be that as it may, we know that although Barnes may not have been the inventor of the term, it was part and parcel of him. It was already redolent in his dialect poems, those masterly and most expressive recitals of simple peasant life and lore, then first being given to the public. What can be more fitting than the definition he himself gives of it in his “Fore-say” to my book, when, as his intellect mellowed in his old age, he could think of nothing so appropriate as to describe folk-lore as “a clear homely word for a wide field of homely knowledge," which he amplified by saying that “folk-lore, taken in its broad meaning is a body of home-taught lore, received by the younger folk from elder ones in common life, and in the forms of knowledge or faith, or mind-skills or hand-skills, and so differing from the lore of schooling and books, which is often called by the people ‘book-learning.’” And again: “To folk-lore belong the customs by which folk may keep up the memory of the times and tides of the year, or of the thought-worthy haps which have befallen their forefathers.”

As I have said, though Barnes does not appear to have written at any length upon folk-lore generally or to have made it a specific study, he did, from time to time, make some contributions to one or more of those journals of the day more especially devoted to popular antiquities.

The earliest I can find of these contributions is in William Hone's “Year Book” in 1832, a reprint of which book was published in 1866, and contains an account of several old customs and superstitions — “the memories of the tides and times of the year” — which obtained in the Dorsetshire of his youth, under the headings of “Harvest Home,” “Haymaking,” “Matrimonial Oracles,” “Midsummer Eve,” “Country Fairs,” “Perambulations,” etc. Again, he sent an account of the single-stick playing and cudgelling and wrestling, and other sports formerly so commonly indulged in by the men at the village “feasts;" and the less manly ones, perhaps, of “jumping in sacks,” “grinning through the horse collar,” “running for the pig with the greased tail” — and, for the women-folk, “the running of blushing damsels for that indispensible article of female dress the plain English name of which rhymes with ‘frock’”— with which description the writer so delicately shrouded the old customary pastime of “running for the smook.” The article includes an account of the “Fair Days,” formerly the source of great delight and amusement to so many of the Dorset villagers, but now so restricted and curtailed in their operations as holidays have become so general all over the countryside, and the occasions for which so many of them had been instituted have passed away.

Later, in the 1863 edition of his “Grammar and Glossary,” Barnes added to the meaning of many of the provincialisms there given a note of any superstition that might be attached to them, particularly to those objects of natural history of which his glossary is so full. He also outlines, in the concluding part of his “Grammar,” several Dorset proverbial expressions such as :

"The vu'st bird the vu'st eäss"

The first bird, the first earth-worm. The first come, the first served.

“Good for the bider,

Bad for the rider."

A reference to the deep alluvial soil like that of Blackmore, indicating its remunerativeness to the inhabitants but inconvenience to the traveller.

"Sluggard's guise,

Lwoth to bed, an' lwoth to rise,"

said of a sluggard.

The following aphorisms or rhymes may also be noticed:

“Gifts on the vinger

Sure to linger.

Gifts on the thumb,

Sure to come."

"Gifts" are the white spots on the finger nails believed to betoken coming presents.

"March wull sarch, Eäpril wull try,

May 'ull tell if you'll live or die."

“Whippence, whoppence,

Half a groat, worth twopence,

More kicks than halfpence.”

The common versical references to a magpie, a lady-bird, a kernel, the large white moth or “miller,” bed-charms, must be well-known to most of my readers, and I need not repeat them here. There are, however, many genuine bits of folk-lore, particularly those referring to objects of natural history, to be found with explanations attached to these provincialisms. For instance, what can be sweeter than the following legend attaching to the spotted liverwort, which appears in the 1886 edition of the “Glossary” published shortly before the author's death, from the pen of the late Mr. H. J. Moule, formerly Curator of the County Museum at Dorchester, written in that charmingly simple style so characteristic of him. “At Ossington, “and no doubt elsewhere in our county, there is a survival of a sweet “simple old-world piece of folk-lore about the spotted liverwort. The cottagers “like to have it in their gardens, and call it ‘Mary's tears . . . But the 'Books call it Pulmonaria,” adds Mr. Moule elsewhere.3 "The legend is 'that the spots on the leaves are the marks of the tears shed by St. Mary ' after the Crucifixion. Further, and this is to me quite an unknown tradition, ' her eyes were as blue as the fully opened flowers, and by weeping, the 'eyes became as red as the buds."

Again, if a young “maiden” ash tree — that is, one not polled — “be split, and a ruptured child drawn through it, he will become healed.” Mr. Barnes states that he has known of two trees through which children have been so drawn. Allusion is also made to the belief that if a shrew-mouse — called in Dorsetshire a “shrow-crop” — happens to run over a person's foot it will cause lameness. Hence, in Hants it is called the “over-runner.”

These isolated bits of folk-lore are scattered about in his “Glossary,” and here and there we may catch pleasing glimpses of them in his dialect poems. But the longer, and more important references to old customary observances are to be found in Hone's “Year-Book.” That relating to the Harvest Home festival, his daughter, Mrs. Baxter, has transferred almost bodily to her “Life” of her father. But in order to thoroughly understand and appreciate this account, one should try and visualize that quiet homely life in the Vale of Blackmore at that time which formed the setting to so many of his poems. That scene is so well set forth by Mrs. Baxter that I cannot do better than give her words here.

After stating (p. 5) that her father was born at Rushay, a farm not far from Pentridge, whence the family afterwards removed to the “Golden Gate” — a house which has since been pulled down — and that subsequently John Barnes, the poet's father, bought a small lifehold house at Bagber (a hamlet in the parish of Sturminster Newton), she continues :

“The Vale of Blackmore, in which all these houses of his forbears were situated, is a kind of Tempé — a happy valley — “so shut in by its sheltering hills that up to quite modern times the outer world had sent few echoes to disturb its serene and rustic quiet. Life in Blackmore was practically the life of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until the nineteenth century was actually far advanced. The farmer helped to till his own land, his wife did not disdain to churn her butter and curd her cheeses, and the days passed in homely and rustic duties, which to our mind have a sweet old-world charm. The family meals were eaten in the oak-beamed old kitchen, where was the settle and the ‘girt wood vire,’ with the hams and bacon hanging overhead; and thus the ears of the boy would have been from infancy accustomed to the sound of that dialect, the love of which clung to him throughout life and was the basis of his fame, being the speech which most easily clothed his poetic thoughts."

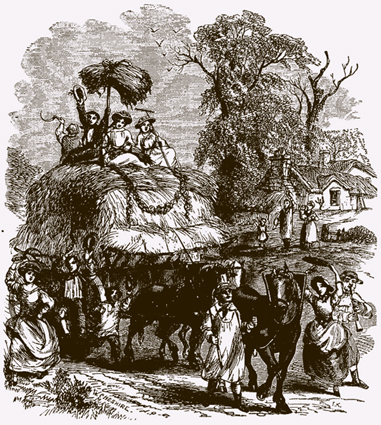

Harvest Home from the

Chambers' The Book of Days

Mrs. Baxter then goes on to say that “Nothing can give so true an idea of the easy rustic life of goodwill and friendship in this ‘old world vale of Blackmore’ than the following description of Harvest Home, which was one of William Barnes' first contributions to Hone's Year Book not long after he had left Bagber, and was certainly a page out of his youthful life.”

“When the last load was sickled, the labourers, male and female, the swarthy reaper and the sun-burnt hay-maker, the saucy boy who had not seen twelve summers, and the stiff, horny-handed old mower who had borne the toil of fifty, all made a happy group and went with singing and loud laughter to the ‘Harvest Home’ supper at the farmhouse. Here they were expected by the good mistress, dressed in a quilted petticoat and a linsey-woolsey apron, with shoes fastened by huge silver buckles which extended over her feet like a pack saddle on a donkey. The dame and her husband welcomed them to a supper of wholesome food, a round of beef and a piece of bacon, and perhaps the host and hostess had gone so far as to kill a fowl or two, or even a turkey which had fattened in the wheat- yard. This pure English fare was eaten from wooden trenchers, by the side of which were put cups of horn filled with beer or cider. When the cloth was removed, one of the men, putting forth his large hand, like the gauntlet of an armed knight, would grasp his horn of beer and, standing on a pair of legs which had long outgrown the largest holes in the village stocks, and with a voice which, if he had not been speaking a dialect of the English language, you might have thought came from the deep-seated lungs of a lion, he would propose the health of the farmer in the following lines:

‘Here's a health unto our meäster,

The founder of the feäst;

And I hope to God, wi' all my heart,

His soul in heaven mid rest.

That everything mid prosper

That ever he teake in hand.

For we be all his sarvants,

And all at his command.’

After this would follow a course of jokes, anecdotes and songs, in some of which the whole company joined without attending to the technicalities of counterpoint, bass, tenor, and treble, common chords, and major thirds; but each singing the air and pitching in at the key which best suited his voice, making a medley of big and little sounds, like the lowing of oxen and the bleating of old ewes mixed with the shrill pipings of lambs at a fair."

This scene is still more jovially represented in two of his dialect poems — “Harvest Home” — “The Vurst Peärt: the Supper” and “Harvest Hwome: Second Peärt — What they did after Supper,” followed, by "A Zong of Harvest Home."4

It will be noticed that Mrs. Baxter in taking this account from Hone's “Year-book” (p. 586) has not adhered to the “word-shape” or the “voice sounds” there used in this harvest toast, but has followed the more modern dialect spelling which marks the later editions of her father's poems. Barnes, writing in 1832, used the harsher, if richer, Doric of the Blackmore Vale country — the language of the district in which he was born and where he passed his early days — there, "meäster" was "miaster," and "teäke" was "tiak," and generally the vowel "i" was prefixed to an "a."

Later, as he grew older and travelled about more, presumably his ear became more attuned to the softer speech of the peasantry stretching away to the Devonshire border, and would seem to have recognised that his dialect poems might be more generally understood and appreciated by the generality of his readers if some-what softened and toned down. So in the third edition of his poems, published by John Russell Smith in 1862, this was given effect to, and a very considerable revision of his poems was made on these lines. Thus “miaster” became “measter” with a diœresis over the centre vowels, together with other softenings which are readily discernible.

This revision has been accepted in all later editions of his poems as well as in his “Glossary,” so much so that readers of the dialect poems in the editions to be obtained now-a-days would hardly recognise, for instance, one of the best known of his early poems — that inimitable eclogue: “A Bit of Sly Coorten” — in its old dress as disclosed in the first edition of 1844.

That Barnes himself felt the necessity for this softening or toning down of his dialect speech is clear from the “Preface” to this third edition in 1862, wherein he says: “My verses were first written for “western English minds; but as I believe so in any of the wider world “now do us Dorset men the honour of reading them, I have taken, for “their sakes, a scheme of spelling which, while it affords the Dorset forms “of the words to Dorset readers, may make them of more English look, "and more legible to others.”

Apropos of this necessity, I trust I need no apology in alluding to what Mr. Hardy himself thinks about it, when in his preface to his “Select Poems of William Barnes,” published in 1908, emphasized by all the high authority which belongs to “one of the few living persons having a practical acquaintance with letters who knew familiarly the Dorset dialect when it was spoken as Barnes wrote it, or perhaps know it as it is spoken now, he says : “Since his death education in the West of England, as else - where, has gone on with its silent and inevitable effacements, reducing the speech of this country to uniformity and obliterating every year many a fine old local word. The process is always the same; the word is ridiculed by the newly taught; it gets into disgrace; it is heard in holes and corners only, it dies; and worst of all, it leaves no synonym. In the villages that one recognises to be the scenes of these pastorals, the poet's nouns, adjectives and idioms daily cease to be understood by 'the younger generation."

For all this, however, we feel that we have one great consolation, and it has come only just in time — and that is Dr. Joseph Wright's great “English Dialect Dictionary” already mentioned — a fitting and worthy contemporary to stand by the side of that other great dictionary — the “New Oxford Dictionary” now, happily, nearing completion.

A close reader of Barnes' poems cannot fail to be struck by so much that concerns the inner life of the country folk, and every phase of that life. Especially is this to be seen in the homely and happy surroundings in which he loved to place those about whom he wrote, for he looked mostly on the bright and pleasant side of things; though, here and there, his poems are full of the deepest pathos and the sincerest sympathy with sorrow. Some of his happiest inspirations are to be found in the great interest he has always shown in child life, both in its work and in its play, especially in that of the village maiden as she began to grow towards adolescence, and in her not unnatural endeavour to peer into what the future might have in store for her, which formed so strong a feature in so many children's games. Amongst these, what Barnes calls “matrimonial oracles” held a large place, and he has fully treated of these in his contributions to Hone. After a somewhat lengthy prelude as to the fateful consequences which may attend married life, and to the natural anxiety of young women, instilled into them at an early age, to know what sort of husbands the fates may have provided for them, he goes on to say (pp. 587-588).

MATRIMONIAL ORACLES. — “In My childhood — a time when, as Petrarch says of old age — little lovers may be allowed to sit together, and say whatever comes into their heads; when the pretty name of Flora or Fanny was not a whit more to me than Tom or Jack; and when a pound of marbles, with half a score of shouting boy-playmates were as pleasing to me as a dance with a party of smiling rosy girls; I recollect some of my female friends, while gathering flowers in a meadow, would stop, arid picking a large daisy, pull off the petals one by one, repeating at the same time the words, ‘Rich man. poor man, farmer, ploughman, thief’ — fancying, very seriously, that the one which came to be named at plucking the last petal would be her husband. Another way of knowing the future husband (inferior only to the dark words of that high priestess of the oracles of Hymen, the cunning gypsey) is to pluck an even ash-leaf, and, putting it into the hand, to say :

‘The even ash-leaf in my hand,

The first I meet shall be my man.'

Then, putting it into the glove, to say:

'The even ash-leaf in my glove,

The first I meet shall be my love.'

And, lastly, into the bosom, saying:

‘The even ash-leaf in my bosom,

The first I meet shall be my husband.’

Soon after which, the future husband will make his appearance, and the lass may observe him as accurately as she will.”

Certain seasons of the year are considered more propitious than others, or more effective in their results, for obtaining a happy solution to these various methods of divination; and Barnes goes on to say that —

“Midsummer Eve is the great time with girls for discovering who shall be their husbands; why it is so more than any other I cannot tell, unless, indeed, the sign Gemini, which the sun then leaves, is symbolical of the wedding union. But however that may be, a, maiden will walk through the garden at midsummer with a rake on her left shoulder, and throw hemp-seed over her right, saying at the time,

Hemp-seed I set, hemp-seed I sow,

The man that is my true love come after me and mow.’

“It is said, by many who have never tried it, and some who have without effect, that the future husband of the hemp-sowing girl will appear behind her with a scythe, and look as substantial as a brass image, of Saturn on an old time-piece."

Readers of “The Woodlanders” will not fail to recall the account given by Mr. Hardy of the observance of this custom by the village maidens of the Hintocks as they left their homes for the woods in which they were to try their fate, a handful of hemp-seed being carried by each girl, and how realistic it proved to be to some at least of the party.

“Or if, at going to bed, she put her shoes at right angles with each other, in the shape of a T, and say —

‘Hoping this night rny true love to see,

I place my shoes in the form of a T ' —

they say she will be sure to see her husband in a dream, and perhaps in reality, by her bedside.

“Besides this, there is another form of divination. A girl, on going to bed, is to write the alphabet on small pieces of paper, and put them into a basin of water with the letters downwards, and it is said that in the morning she will find the first letter of her husband's name turned up, and the others as they were left.”

A full description of what took place on the old customary Fair Days — the country fair being the source of infinite joy and expectation to the country folk as well as to the inhabitants of the various market towns in their vicinity — is given with a gusto and an accuracy that denoted that the poet himself must often have been an attendant of them. “Perambulations or Beating the Bounds”— the well-known custom on Holy Thursday of going round the boundaries of the parish or manor with witnesses, in order to determine and preserve the recollection of its extent — are also described at some length. This proceeding is commonly regulated by the steward or other official of the parish, when steps are usually taken (and often with amusing, if not painful results) in order to impress upon the recollection of the younger members of the party, usually boys, what they had come out to witness. Not long ago a very amusing incident, happily unattended by any serious consequences, occurred in “beating the bounds” of the parish or borough of Bridport, when in crossing a mill-dam in a boat the boat capsized, and the Mayor and his attendants had to make the best of their own way to the side. I think this certainly was an incident not likely to be forgotten.

In another place (p. 800) Barnes speaks of the old custom of “Lent-Crocking” at Shrovetide which, as it is one of the very old customs obtaining in the county — though, I am afraid, practically obsolete now — I will give in his own spirited words :

LENT-CHOCKING. — "In Dorsetshire, the boys sometimes go round in small parties, and the leader goes up and knocks at the door, leaving his followers behind him armed with a good stock of potsherds — the collected relics of the washing-pans, jugs, dishes and plates that have been the victims of concussion in the unlucky hands of careless housewives for the past year. When the door is opened the hero, who is perhaps a farmer's boy, with a pair of black eyes sparkling under the tattered brim of his brown milking hat covered with cow's hair and dirt like the inside of a blackbird's nest, hangs down his head, and with one corner of his mouth turned up into an irrepressible smile, pronounces in the dialect of his county the following lines, composed for the occasion, perhaps, by some mendicant friar whose name might have been suppressed with the monasteries by Henry VIII. :

‘I be come a-shrovin'

Vor a little pankiak,

A bit o' bread o' your biakin

Or a little .truckle cheese o' your own miakin,

If you'll gi' me a little, I'll ax no mwore,

If you don't gi' me nothin' I'll rottle your door,'

Sometimes he gets a bit of bread and cheese; and at some houses he is told to be gone, when he will call up his followers to send their missiles in a rattling broadside against the door.

"The broken pots and dishes originally signified that, as Lent was begun, those cooking utensils were of no use, and were supposed to be broken; and the cessation of flesh-eating is understood in the begging for pan-cakes and bread and cheese."

Elsewhere, Barnes calls attention to the Mummers, or, as they were sometimes called “Guisers” or “Maskers,” whom in his Glossary (s. v. Mummers) he describes as "a set of youths who go about at Christmas, decked with painted paper and tinsel, and act, in the houses of those who like to receive them, a little drama, mostly, though not always, representing a fight between St. George and a Mohammedan leader, and commemorative, therefore, of the Holy Wars. One of the characters, with a hump-back and bauble, represents “Old Father Christmas.” The libretto of the Dorset Mummers is much the same as that of the Cornish ones, as given in the specimens of the “Cornish Provincial Dialect” published in 1846.

Barnes, no doubt, alludes to a small volume by “Uncle Jan Trenoodle” (W. Sandys), published by John Russell Smith in 1846, in which, at pp. 53— 59, appears an “Account of a Christmas Play,”5 containing extracts which certainly in many respects indicate a common origin for some of the Dorset versions which are still extant in the western part of the county, though there appear also to be a few characters which are foreign to it. It is sad to think that up to the very recent revival of interest in the folk-songs and folk-games of the people — which I sincerely trust may continue — these and similar performances are fast fading away.

Barnes does not seem to have farther interested himself in the Mummers — so far as I can discover — but Mr. Thomas Hardy, equally conversant with old Dorset customs — of which he makes such splendid use in his Wessex novels — introduces a most effective scene with the Christmas Mummers in his “Return of the Native” as performed in a cottage amidst the gloomy wilds of “Egdon Heath.” From the somewhat perfunctory way in which the play is given and received, Mr. Hardy, is led to form the opinion that the whole thing is a genuine .survival, and not a mere revival, of an ancient custom.

In 1874 I would seem myself to have taken an interest in these Dorset mumming plays, for I find that I sent to "Notes and Queries" (5th Series, ii, 505) a list of characters in two plays (the plays being too long to reproduce there) as performed by mummers at Christmas time in two distinct parishes in West Dorset. It will be seen that there is a considerable variation riot, only in the numbers but also in the names of the performers in the two parties. In the second version the English champion is represented by the Sovereign — instead of the Saint — George, no doubt a modern innovation. Again, in 1880, I had an opportunity of giving fuller details of these two plays by reading a paper upon “Christmas Mummers in Dorsetshire” before the newly formed Folk-Lore Society, which was subsequently printed in the “Folk-Lore Record” (vol. III, p. 87) in which I gave both: these two plays in full. The plays were preceded by a general introduction to the subject, in which numerous authorities and references to plays in other counties were cited, and was followed by a very interesting discussion, which was also printed. To this I would refer such of my readers who may be interested in the subject of mumming plays from more than a Dorset point of view.

Further, in 1904, in answer to a request by a correspondent for the words of the dialogue formerly used in the neighbourhood of Beaminster in West Dorset — a custom which he stated was then almost extinct in the neighbourhood — I contributed an additional play to the “Somerset and Dorset Notes and Queries” (Vol. IX, p. 9) which had been acted at Christmas time at my own house at Symondsbury, in West Dorset, in the mid eighties. Similar performances have been given there by boys, and by others quite adult. In all these versions, whilst varying in details, there is a strong family likeness. It should be remembered, too, that in most of these versions, as originally rendered by the performers, are contained many bits of dialect speech.

WITCHCRAFT. — Scattered through the poems we see many traces of the belief in the efficacy of “charms” as preventives against or cures for witchcraft or spells cast by the “overlooker,” or from the malefic influence of the “evil eye.” Many of these have a special reference to objects of natural history, and must be well-known to many of my readers. The belief in the power of the witch or “wise-woman” — to say nothing of the male witch or “wizard” — is wide-spread, and this not only amongst the ignorant peasants and town-dwellers, but even amongst persons of a much higher station in life. Barnes must have been a keen observer in these matters, for we find that in his poem of “The Witch,” 6he mentions no less than a dozen forms of bewitching or overlooking which may befall, in person or estate, any peasant or his employer who may have been so unfortunate as to incur the displeasure or resentment of such a “sly wold witch” as he there depicts. At the same time, he describes two of the-most widely recognised “charms” for the cure or prevention of the spell. All these are so vividly and concisely portrayed in the poem that I feel I cannot do better than reproduce that part of it which treats of them.

“An zoo, they soon began to vind

That she'd agone an’ left behind

Her evil wish that had such power,

That she did mëake their milk an’ eäle turn zour,

An’ addle all the aggs their vowls did lay.

They coulden vetch the butter in the churn,

An’ all the cheese begun to turn

All back agean to curds an’ whey;

The little pigs, a-runnen wi’ the zow,

Did sicken zomehow, nobody know'd how,

An’ vail, an' turn their snouts towards the sky

An’ only gi’e woone little grunt an’ die.

An’ all the little ducks an' chicken

Were death-struck vout in yard a-pickén

Their bits of food, an’ veil upon their head,

An’ flapped their little wings an’ drapp'd down dead

They coulden fat the calves, they woulden thrive;

They coulden seave their lambs alive;

Their sheep wer all a-coath’d, or gi’ed no wool:

The hosses veil away to skin and bwones,

An' got so weak they coulden pull

A half a peck o’ stwones:

The dog got dead alive an’ drowsy,

The cat veil zick an’ woulden mousy;

An' every time the v’ok went up to bed

They wer a hag-rod till they wer’ half dead.

They us’d to keep her out o’house, ‘tis true

A-nailén up at door a hosses shoe;

An’ I've a-heard the farmers wife did try

To dawk a needle or a pin

In through her wold hard wither’d skin,

An’ draw her blood, a-comén by;

But she could never vetch a drap

For pins would ply an’ needles snap

Agean her skin; an’ that, in coo’se,

Did meake the hag bewitch ‘em woo’se.”

The only other published reference to witches by Barnes that I can find is from a short paper “On the Maze, or Miz-maze at Leigh, Dorset,” contributed by him to the Dorset Field Club,7 to be found in Vol. IV., p. 156, of its “Proceedings” (1882), where he says:

“Many years ago, I was told " by a man of this neighbourhood that a corner of Leigh Common was called ‘Witches' Corner,’ and long after that, a friend gave me some old depositions on witchcraft, taken before Somerset magistrates from about the year 1650 to 1664. The cases were of Somerset, and touched in some points Dorsetshire, and one of the witches' sisterhood said that they sometimes met on Leigh Common. This proof of the meeting of witches' in Leigh Common as the ground of the traditional name of ‘Witches Corner’ is interesting as a token of truth in tradition.”

From witches, it is no far cry to fairies and the lore belonging to and surrounding them. As Barnes says in his “Glossary” (s.v. Veäry-ring), “the belief in fairies, one of the most beautiful and poetical of superstitions, still lingers in the West . . . . . Toadstools are pixy stools, or fairy stools; for as they enrich the soil, and bring the fairy ring by rotting down after they have seeded outward from its centre, so that the ring of actual fungi is outside of the fairy-ring, so it was natural for those who believed the ring to be brought by the dancing of fairies to guess that the fungi were stools upon which they sat down when tired."

It is firmly believed by many Dorset folk that fairies can get into the house not only down the chimney (against which particular form of entry many charms are directed — viz., a bullock's heart, studded with pins and thorns, placed some way up the chimney shaft) —but also through the key-hole. Barnes certainly gives effect to this belief in his dialect eclogue on “The Veäries” (p. 74) by a most graphic and pathetic description of the little fairy elf who was discovered in a house in the early morning, having effected an entrance through the keyhole, but who was unable to get out again under the circumstances detailed in the poem; and which affords as worthy a little gem for Cruickshank's pen as any of those inimitable elfin scenes with which he has so exquisitely illustrated the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm.

“Why, when the vo’k wer all asleep, a-bed,

The veäries us’d to come, as ‘tis a-said,

Avore the vire wer cwold, an dance an hour

Or two at dead o’ night upon the vloor;

Var they, by only utterén a word

Or charm, can come down chimney lik’ a bird;

Or draw their bodies out so long an’ narrow,

That they can vlee drough key-holes lik’ an arrow.

An’ zoo woone mid-night, when the moon did drow

His light drough window, roun’ the vloor below,

An’ crickets roun' the bricken he'th did zing,

They come an’ danced about the Hall in ring,

An’ tapped, drough little holes noo eyes could spy,

A kag o’ poor aunt's mead a-stannén by.

An’ woone o’m drink’d so much, he coulden mind

The word he wer to zay to meäke en small;

He got a-dathered zoo, that after all

Out t’others went an’ left en back behind.

An’ after he'd a-beat about his head

Agëan the key-hole till he wer half dead,

He laid down all along upon the'vloor

Till granfer, comén down, unlocked the door,

An’ then he zeed en (‘twer enough to frighten en)

Bolt out o’ door an’ down the road lik’ lightenén.”

I think I have now said enough to give some idea from his published writings to what extent William Barnes was imbued with the knowledge of his county's folk-lore, and of the customs, habits and pastimes of its people. But this was but a small portion of it all. He was, as I have said before, brimful of it. The extent of that knowledge can now never be excelled — I doubt if ever equaled — even by his great successor, Thomas Hardy, for the materials upon which these two great writers have worked no longer exist. And it is left for me now, alas, to do little more than to collect. This connection — longo intervallo — of myself with these two great masters of the subject reminds me of a speech that the late Mark Twain is reported to have once made in London, when in returning thanks for the toast of “Literature” at a dinner given by the Pilgrims' Club (I think), he commenced by saying (after an impressive pause) “Shakespeare is dead.” (And after another prolonged pause), “Milton is no more.” And then (after a still longer one), “And I am not feeling very well myself.” Upon which he promptly sat down.

With this story, I think I may fitly close my article.

Footnotes:

1. Vol. XV (1917) pp. 34, 44.

2. I make no apology for the use of this word. It was Barnes's own. I had grown so tired of that excellent synonym " Fore-word," so fitting when first used by Thomas Hardy as a preface to his Wessex studies, but which now, by reason of that very excellence, had become so hackneyed, that I was more than pleased when I lighted upon the word " Fore-say " already used as an introduction or preface by Barnes himself in his u Outlines of English Speech-craft " (1878) and "Outlines of English Redecraft" (1880)—those wondrous little books in which he sought to uphold "our own strong Anglo-Saxon speech and the ready teaching of it to purely English minds by their own tongue."

3. “The Folk-Lore Journal,” vol. vi", p. 18.

4. Pp. 78-82 of the collected edition of the poems by Kegan Paul & Co. (1879 et seq).

5. In the glossary attached, these Christmas plays are called "giz-" or "guise-dances."

6. Pp. 173-174 of the complete edition.

7. Barnes, indeed, may be said to be one of the founders of this Club, which was inaugurated in 1875 ; and to those " Proceedings " he contributed short papers, mainly on archaeological subjects, from that time almost up to his death. I look back with a sad pleasure to the fact that it was under his and the late Mr. J. C. Mansol-Pleydel's (our first President) sponsorship that I became one of the original members of it, of whom but very lew now survive.

First published in The Dorset Year Book 1920 -21

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | Barnes Night: A Celebration of the Life and Work of William Barnes

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | A Dorset Spring through the Poetry of William Barnes

11:00 till 12:30

Annual Service of Thanksgiving of William Barnes

Starts 00:00

Cerne Abbas Festival - William Barnes' Poetry Readings

13:00 till 15:00

Wreath Laying at the William Barnes Statue

10:00 till 17:00

William Barnes at Stock Gaylard Oak Fair 2026