WESSEX WORTHIES: William Barnes

by J. J. Foster

William Barnes was bom at Rushay, near Pentridge, in the Vale of Blackmore in 1800 or 1801 ;* he lived for eighty-five years, and, it would seem, hardly quitted his dear native county the whole time.

The outer, greater world seems to have had but little attraction for, and no hold whatever on Barnes, his hopes, fears or pursuits. The result was a certain narrowness, if you will” but also a concentration which made for the perfection of his life-work. And what was that work ? a rendering in poetic form of the impressions made on him by rustic life and its surroundings in those days, which already seem so far removed, before the shriek of the railway engine was heard in the land, and when the "Road Hog" was unknown.

According to his daughter, who, under the pseudonym of "Leader Scott," 1 wrote a sympathetic life of her father, " Philology was Barnes's most earnest study," and those who will peruse the list of his publications which she gives (it extends from 1822-1886) will see how her father wrestled with Philology all those years. But his work in that direction lacks scientific value and has never won recognition. It has been said of it that " it is too much governed by imagination and bias, too theoretical " ; and in truth liis Philology already seems to be in a fair way to be forgotten. But although, according to the same authority, the making of poems was but a small part of his intellectual life, poetry was his real métier, and sympathy with honest labour impelled him to give utterance to its sorrows and its joys as realised by him from his close and life-long acquaintance with them. Barnes's poetry, with its charm, and truthful rendering of rural nature, is now so fully recognised as to have become classic. The first volume was issued in 1844, in the Dorset dialect. This was followed by " Poems, partly of Rural Life (in National English)." In this last work the medium employed was ordinary speech, but the superiority of the dialect made itself felt. It was, as his daughter has remarked, " the basis of his fame” the speech which most easily clothed his poetic thoughts."

According to his daughter, who, under the pseudonym of "Leader Scott," 1 wrote a sympathetic life of her father, " Philology was Barnes's most earnest study," and those who will peruse the list of his publications which she gives (it extends from 1822-1886) will see how her father wrestled with Philology all those years. But his work in that direction lacks scientific value and has never won recognition. It has been said of it that " it is too much governed by imagination and bias, too theoretical " ; and in truth liis Philology already seems to be in a fair way to be forgotten. But although, according to the same authority, the making of poems was but a small part of his intellectual life, poetry was his real métier, and sympathy with honest labour impelled him to give utterance to its sorrows and its joys as realised by him from his close and life-long acquaintance with them. Barnes's poetry, with its charm, and truthful rendering of rural nature, is now so fully recognised as to have become classic. The first volume was issued in 1844, in the Dorset dialect. This was followed by " Poems, partly of Rural Life (in National English)." In this last work the medium employed was ordinary speech, but the superiority of the dialect made itself felt. It was, as his daughter has remarked, " the basis of his fame” the speech which most easily clothed his poetic thoughts."

It was when he wrote in his mother tongue that he was at his best ; in it he was able fully to deal with the simple life he portrays. He was so entirely the Dorset farmer's son, that anything which came from his heart, as his writings about the scenery round Gillingham did, was bound to be, and is, amongst the freshest, brightest work, of its own idyllic kind, in our language” with which well deserved praise we may now turn to trace the author's origin and career.

The mother of William Barnes was Grace Scott, born at Fivehead Neville "A woman," says her grand-daughter, " of refined tastes," possessing an inherent taste for poetry and art, and, there is no doubt, most tenderly beloved by her husband.

Barnes was educated at " Tommy Mullet's " School at Sturminster. From thence, about 1814 or 1815, he passed into the office of a local Solicitor, Mr. Dashwood ; and in 1818, he entered the employment of Mr. Coombs, Solicitor, Dorchester. When he was but eighteen years of age he saw, springing lightly down from a stage coach at the " King's Arms," in the High Street of Dorchester, a child who, he felt at the time and rightly felt, was destined to be his wife. Her name was Julia Miles, the daughter of an Excise Officer ; she was of slight and graceful figure, with blue eyes and wavy brown hair.

Barnes' first poem was dedicated to her, and published in the " Weekly Entertainer," in 1820. Three years after we find him moving to Mere, in Wiltshire, at the instance of his friend, Mr. Carey, where he took over the school of a Mr. Robertson. And here, he records in his diary, he " took up in turn Latin, Greek, French, Italian and German." He practised drawing and engraving too, and in 1826, as we learn from the same source, he cut some little blocks for Mr. Barter, a printer in Blackmore, and was mostly paid in

"book-binding and cheese," Again, in 1827 and 1828, he records having engraved some blocks for Mr. John Rutter of Shaftesbury” most of them were for " Delineations of Somerset," published in 1829. He had also a little copper-plate press, and " dreamed," he says, " f or a week or a fortnight of trying my fortune as an Engraver at Bath." He was moreover a musician; and played the organ and other instruments.

In 1835, yearning for a wider sphere than Mere afforded, he decided to move to Dorchester, where he settled in a house in Durngate Street. Apropos these scholastic days, an old pupil, the Rev. J. B. Lock, Bursar and Senior Fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge, has given in Leader Scott's book a picture of his master's methods of teaching. He concludes his account by observing : " these lectures of my old master were as wonderfully adapted to his audience, as they were clear and accurate in substance."

On the other hand Sir Frederick Treves has given a different version of the value of Barnes's manner of teaching in some amusing recollections which he contributed to the Year Book of the " Society of Dorset Men in London " in 1915-16, a few lines from which may be quoted :”

"My vague recollection of William Barnes is of an old clergyman of great courtliness, ever gentle and benevolent, who bore with supreme simplicity the burden of a learning which was almost superhuman . . ."

"About once a week Barnes opened the school by a lecture on some subject of practical interest. On the day of my first appearance at school there was such a lecture. It was on Logic. I was required to write from dictation the following sentence : ' Logic is the right use of exact reasoning.' This is the first important contribution to the sum of human knowledge that I ever received. For a boy of seven it was undoubtedly ' strong meat.' It was, I am hardly ashamed to say, wholly unintelligible. The lecture that followed only served to add mystery to the text. I formed the idea that logic was some kind of medicine ; physic” as administered in those days to the young ..."

Although I knew William Barnes almost from my earliest days I cannot as a pupil claim any knowledge of the value of his teaching. But, judged by ordinary standards, and the notes for lectures which he reprinted in such works, for example, as the " Ancient Britain and the Britons," and " Early England and the Saxon English " his methods might, it is true, excite an interest in the minds of studious boys, but, I think, do little more.

Although I knew William Barnes almost from my earliest days I cannot as a pupil claim any knowledge of the value of his teaching. But, judged by ordinary standards, and the notes for lectures which he reprinted in such works, for example, as the " Ancient Britain and the Britons," and " Early England and the Saxon English " his methods might, it is true, excite an interest in the minds of studious boys, but, I think, do little more.

By this time his poems in the Dorset dialect had appeared” that is to say, after his thirty-fourth year. They were first issued in the " Dorset County Chronicle " with classical titles ; thus, the well-known humorous Eclogue, "A bit o' sly Coorten " was styled " Rusticus Procus " (which, being interpreted, is " the Rustic Wooer ").

The reasons which led Barnes to adopt, and finally to adhere to the Dorset dialect in preference to modem English, have been discussed by a master of the subject, a Dorset man himself and the highest authority that could be quoted, Mr. Thomas Hardy. He says : "It may appear strange to some, as it did to friends in his lifetime, that a man of insight who had the spirit of poesy in him should have persisted year after year in writing in a fast-perishing language, and on themes which in some remote time would be familiar to nobody” a language with the added disadvantage by comparison with other dead tongues that no master or books would be readily available for the acquisition of its finer meanings He himself simply said that he could not help it, no doubt feeling his idylls to be extemporisation, or impulse, without prevision or power of appraisement on his own part. Yet it seems to the present writer that Barnes, despite this, really belonged to the Literary school of such poets as Tennyson, Gray and Collins, rather than to that of the old premeditating singers in dialect. Primarily spontaneous, he was academic closely after ; and we find him warbling his native wood-notes with a watchful eye on the predetermined score, a far remove from the popular impression

of him as the naif and rude bard who sings only because he must, and who submits the uncouth lines of his page to us without knowing how they come there."2

But the reasons have also been given by Barnes himself. They are interesting to philologists, and will be found set forth in the Preface to his "Philological Grammar," a remarkable work to which we shall shortly recur.

Resuming his life story, we may note that in 1837, he removed to a more commodious house in South Street, Dorchester, exactly opposite that ancient foundation” the Grammar School. In the same year his name was put on the books of St. John's College, Cambridge, as " a ten years' man."

His degree of B.D. was not conferred until October, 1850.

Archaeologists may note with interest that the name of William Barnes is closely associated with the foundation of the Dorset County Museum. A house was taken in 1845, in Back South Street, and here the Rev. Charles Bingham, and Barnes, who were appointed honorary secretaries, set to work on the foundation of a collection which has now grown into such importance in some respects” especially in relation to Geology and Prehistoric Antiquities” as to make it one of our most important provincial Museums. In 1847 Barnes, having been offered the " Donative " of Whitcombe, was ordained as deacon at Salisbury, and priest about a year later. This tiny parish is an adjunct to the living of Came, and it was at the instance and through the offer of Captain Damer of Came House, that Barnes accepted it.

In 1852 he was overwhelmed by the loss of his beloved wife, whose memory he cherished to the close of his life with deep and constant devotion, thus up to the time of his death, the word " Giulia " was written, "like a sigh" says Leader Scott, at the end of each day's entry in his Diary.

The following year (1853) saw the manuscript of Barnes's " Philological Grammar," in the hands of his publisher, Mr. J. Russell Smith. The author accepted five pounds for the copyright of this remarkable book, which aimed at being a Universal Grammar, and is described by his daughter and biographer as being " one of the most extraordinary works a man has ever conceived."

It was, I believe, a failure. About this time trouble came upon the poet. His literary works did not pay” he had family expenses to meet, his sons to provide for” one entering at Cambridge (St. John's). The numbers of his pupils diminished, and grave anxiety resulted. His daughter records his bitterly exclaiming, " They might be putting up a statue to me some day when I am dead, while all I want now is leave to live” I asked for bread and they gave me a stone."

The heavy clouds of debt and disappointment which undoubtedly overshadowed the life of William Barnes during the years at which we have arrived, were destined to pass away early in 1862” for then Captain Damer redeemed his promise, and at the end of this year Barnes took up residence in the picturesque cottage rectory, which was destined to be his home for three and twenty years” until he passed away in November, 1885. Having known him well and personally for many years it was the present writer's good fortune to visit the poet in this delightful and reposeful spot, and to witness for himself the serene happiness in which he spent the close of his career in his dear Dorset home, surrounded by friends, of whom Thomas Hardy was one of his nearest and most intimate. It may be noted here, as evidence of the affection borne him by all who knew him, that not only were literary and " great folk " his admirers, but that his poorer neighbours, and his parishioners were always glad to see him, and to pour into his sympathetic ear their troubles and their joys. One of them is reported to have said " We do all o' us love the passion,

that we do ; he be so plain." Thus we see in this good man, not only love of Nature, but love of Humanity, and it was this precious quality which called out his poetry. He was, as some one has said, " Theocritus by conviction as well as by birth," yet we must not forget that, as Mr. Hardy has pointed out, whilst his poems mean inspiration, they mean art as well, with all their seeming simplicity ; and are drawn from fountains of poetic lore in other languages.

One curious feature in his work remains to be noticed, and that is the total absence of any reference whatsoever to the sea in all his poems and writings, so far as I know. It is very remarkable, seeing that for so many years he lived almost within sound of the sea, and for the last twenty-five years of his life, a walk of a mile or two from his rectory would bring him in sight of

it, say from Culliford Tree or the Ridgeway. But no, born and brought up "in the Vale," he seems unconscious, as it were, of the existence of the sea.

To sum up then, Barnes was a man and a writer of whom Dorset may be rightly proud. His poems were the pure expression of a true and gentle mind, seeing Nature through a poet's eyes. And, though his head was stored with the lore of a sage, his heart remained in his old age as simple as that of a child.

A few personal details about the Poet may be offered in conclusion. Amongst my many recollections of Barnes, one of the most vivid is that of a spring afternoon spent in the little study at Came Rectory, looking out over Conquer Barrow, in the company of Barnes and the writer of the " Introductory Note " to this book. These philologists compared lists of Dialect words, which they discussed with infinite zest. It is a scene the charm of which still lingers in the writer's memory.

The letter of which a facsimile is given is interesting with its strongly marked character. Mr. Tennant says of his writing " He didn't dot his ' i's,' nor cross his ' t's,' and it took him (Mr. Tennant) two days to make out the word 'Cincinnatus.' " But he adds, " I like your hand-writing ; it is unlike anybody else's. It puts me in mind of a fly escaped from drowning in a bottle of ink, and crawling over your paper."

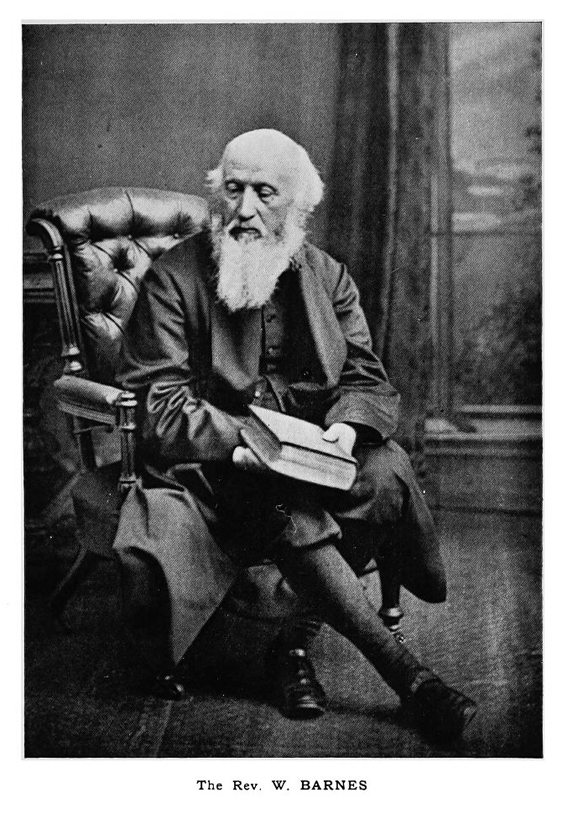

In the photograph of Barnes here reproduced, he is well advanced in years. It is a very faithful portrait ; nor are the picturesque details of dress, familiar knee breeches and buckles wanting.

Another and most interesting portrait is the statuette by the late Roscoe Mullins. This figure, whilst it does not show the head so well as in the photograph of Barnes seated, is an eminently characteristic one of the general appearance of the Poet, and represents him as he was so often seen and so well known in the streets of Dorchester. It was prepared as an alternative design by Mr. Mullins, but the existing statue in front of St. Peter's Church, also his work, was chosen in preference to it. " Degustibus non disputandum est," but, in the present writer's opinion, the figure in the statuette seems at least as faithful as that which was chosen for the existing statue, and certainly more artistic in treatment.

"But now I hope his kindly feace

Is gone to vind a better pleace.

But still, wi' vo'k a-left behind

He'll always be a-kept in mind."

Footnotes:

1."Leader Scott," daughter of the Poet, gives the latter date. Thomas Hardy, in an obituary notice contributed to the Athenceum, in October, 1886, observes that " the earlier date is said to be the correct one."

2." Select Poems of William Barnes," Preface by Thomas Hardy, pp. viii an4 ix,

First published 'Wessex Worthies (Dorset) with some account of others connected with the history of the county, and numerous portraits and illustrations' J. J. Foster, 1920

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | Barnes Night: A Celebration of the Life and Work of William Barnes

Starts 09:00

ONLINE | A Dorset Spring through the Poetry of William Barnes

11:00 till 12:30

Annual Service of Thanksgiving of William Barnes

Starts 00:00

Cerne Abbas Festival - William Barnes' Poetry Readings

13:00 till 15:00

Wreath Laying at the William Barnes Statue

10:00 till 17:00

William Barnes at Stock Gaylard Oak Fair 2026