Around The World With William Barnes: Part 2 - Greece

Byron, Barnes, Hardy - Athens and the Influence of Greek Culture

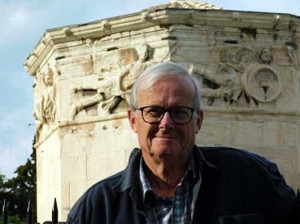

Jim Potts

Lord Byron is still generally held in high esteem in Greece. Greek academics can sometimes be ambivalent about his private perceptions and critical comments, as revealed in his letters rather than in his poems.

Those Greek scholars who are familiar with the works of William Barnes have tended to perceive him as an Anglo-Saxon language fanatic, hostile to the Greek language, a kind of linguistic nationalist or purist vocabulary-cleanser who wanted to eradicate or purge all traces of the Greek and Latin languages from the English language - albeit with the intention of making it more understandable to the less highly-educated reader or listener.

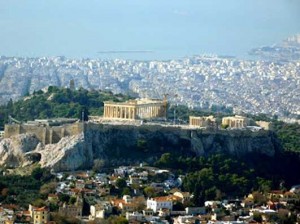

So why was I thinking about Byron, Barnes and Hardy when I was in Athens in November 2017, primarily to watch the beginning and ending of the 42.195kms Athens Authentic Marathon? My daughter had flown in from Washington DC to run in the marathon (like 18,500 other runners, many of them conscious of the story of Pheidippides/Philippides, determined to retrace his famous run from Marathon to Athens). In the words of Robert Browning (Pheidippides):

Unforeseeing one! Yes, he fought on the Marathon day:

So, when Persia was dust, all cried "To Akropolis!

Run, Pheidippides, one race more! the meed is thy due!

'Athens is saved, thank Pan,' go shout!" He flung down his shield,

Ran like fire once more....

???????, ???????!

The 2017 marathon provided the ideal opportunity for us to get together, to show our support, and to explore the centre of Athens. I had had little time to wander around the city when I was working there in the summer of 1985, when Athens was celebrating its role as the Cultural Capital of Europe.

Lord Byron’s legacy may be valued more highly in Greece than that of any other British poet, but both Barnes and Hardy studied Greek literature (Hardy was interested in Hellenic traditions and he was particularly influenced by Aeschylus and Sophocles and the other Ancient Greek dramatists; he also translated a fragment of Sappho); William Barnes had a good knowledge of the Greek language (Ancient and New Testament Greek, rather than the Modern Greek or Romaic that Byron soon picked up in the country). Two editions of his poems carry quotations in the Ancient Greek of the bucolic poets Theocritus and Moschus on the title pages. Barnes must have admired them, and wanted to emulate them.

Contemporary British poets like Tony Harrison have carried on this tradition, which may be traced back to George Chapman and even earlier (Chapman’s translations of The Iliad and The Odyssey were first published in complete form in 1616; publication had begun in instalments in 1598).

William Barnes demonstrated his knowledge of Greek on pages 235-237 of

"A philological grammar, grounded upon English and formed from a comparison of more than sixty languages. Being an introduction to the science of grammar and a help to grammars of all languages, especially English, Latin and Greek, 1854."

?n An Outline of English Speech-Craft, Barnes seems to favour the clarity and precision of the Greek over the English language when he comments on the challenges of translating the Greek Gospel into English.

“It seems that much wrong is done to the Greek of the Gospel by the putting, for the same Greek word, sundry English ones at sundry passages; and by what right do we try an Evangelist’s or an Apostle’s wisdom in the use of the same word, by which he must have meant to give the same meaning? Or why should we make him to mean by ??????, at one time, a trying of a soul and at another time a fordooming of him?”

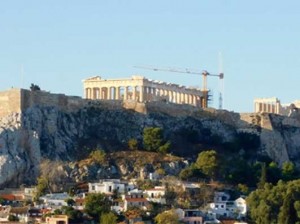

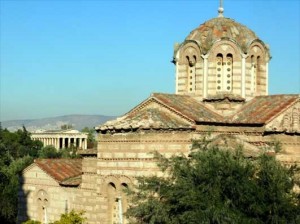

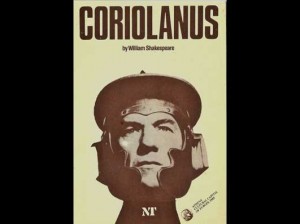

All three poets (Byron, Barnes and Hardy) had an informed interest in archaeology and architecture generally, but also in ancient Greek architecture. When I was Acting Representative of The British Council in Greece during the celebrations and events for the “Cultural Capital of Europe” in 1985, I did of course visit the Acropolis and other archaeological sites, but my workload was very heavy and I had little leisure time to explore the city. A highlight of the British cultural contribution was the remarkable, high-energy, open-air performance of Shakespeare’s Coriolanus at the Herodus Atticus Theatre in Athens. In Sir Ian’s own words:

“In September 1985, after 102 performances on the South Bank, we did two open-air performances below the Acropolis at the Herodus Atticus Theatre in Athens. I was exhausted by the part, although not with it. Playing Shakespeare to 6000 in the open air, with inadequate amplification and chasing up and down ancient steep and deep stairs between the throng, with banner and sword aloft, is a young man's game. During the final show I drank five litres of water and a jar of Greek honey that I filched from Greg Hicks. Even so, after it was over I leant against the backstage wall unable to move and I was half-carried back to the dressing-room and an ouzo. That is the day I first felt mortality as an actor - not that I gave into it”.

Sir Ian Mckellen Official Website: Coriolanus

Barnes and Hardy never visited Greece (except in the virtual sense through their wide reading), but both of them had a serious interest in Greek architecture.

Architecture

William Barnes

O noble art! how greatly I delight

In noble works of thy gigantic hand!

The lofty columns' massy shafts, that stand

Beneath entablatures of stately height;

The tap'ring spire that reaches out of sight;

The lofty roof; with arches that expand

To dumb-beholden width; and windows grand

And glorious with many-colour'd light!

O noble art! how long thy works out-dwell

The sons of men! The piles that linger still

In early-citied Egypt's rainless clime,

And on the holy soil of Greece, will tell

How masterly thou workest, since thy skill

Can mock the working of all-wasting time.

(Bernard Jones gives the final line as “So braves the working of all-wasting time”).

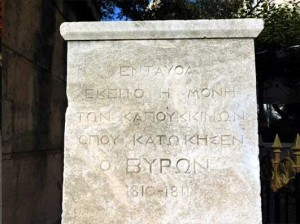

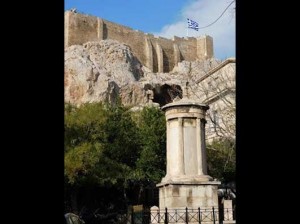

In Athens in November, 2017, I was particularly interested to view the Lysicrates Choragic Monument, and the site of the Capuchin Monastery where Byron had stayed in 1810-1811, where he wrote The Curse of Minerva, in March 1811.

We were fortunate to be able to spend time at the stunning new Acropolis Museum. From our hotel roof garden, and from the top of Lycabettus Hill, the views of the Parthenon were truly spectacular. I revisited the Areopagus (the rocky Hill of Ares), amongst other sites.

Thomas Hardy wrote two important poems concerning the Parthenon Marbles and about the ‘echoes’ of the sermon given by the Apostle Paul at the Areopagus;

In The British Museum

Thomas Hardy

'What do you see in that time-touched stone,

When nothing is there

But ashen blankness, although you give it

A rigid stare?

'You look not quite as if you saw,

But as if you heard,

Parting your lips, and treading softly

As mouse or bird.

'It is only the base of a pillar, they'll tell you,

That came to us

From a far old hill men used to name

Areopagus.'

- 'I know no art, and I only view

A stone from a wall,

But I am thinking that stone has echoed

The voice of Paul,

'Paul as he stood and preached beside it

Facing the crowd,

A small gaunt figure with wasted features,

Calling out loud

'Words that in all their intimate accents

Pattered upon

That marble front, and were far reflected,

And then were gone.

'I'm a labouring man, and know but little,

Or nothing at all;

But I can't help thinking that stone once echoed

The voice of Paul.'

------------------------

Christmas in the Elgin Room

British Museum: Early Last Century

Thomas Hardy

‘What is the noise that shakes the night,

And seems to soar to the Pole-star height?’

– ‘Christmas bells,

The watchman tells

Who walks this hall that blears us captives with its blight.’

‘And what, then, mean such clangs, so clear?’

‘– ’Tis said to have been a day of cheer,

And source of grace

To the human race

Long ere their woven sails winged us to exile here.

‘We are those whom Christmas overthrew

Some centuries after Pheidias knew

How to shape us

And bedrape us

And to set us in Athena’s temple for men’s view.

‘O it is sad now we are sold –

We gods! for Borean people’s gold,

And brought to the gloom

Of this gaunt room

Which sunlight shuns, and sweet Aurore but enters cold.

Rather than quote Lord Byron’s harsh and uncompromising assessment of Lord Elgin, I refer readers to The Curse of Minerva

On the Trail of Byron in Greece

Starts 00:00

William Barnes Harvest Celebration

17:00 till 19:00

The Year Clock

10:30 till 12:00

Annual Service of Remembrance of William Barnes

10:00 till 17:00

William Barnes at Stock Gaylard Oak Fair 2025

15:00 till 17:00

Celebrating William Barnes, Poet and Priest at Whitcombe Church

14:30 till 15:30

Keepen Up O' Chris'mas